© Dyslexia-Research.com - Dr Neil Alexander-Passe - Contact at: neilpasse@aol.com

Dyslexia-Research.Com - The home of humanistic dyslexia research

http://www.jkp.com/jkpblog/2015/08/the-lifelong-social-and-emotional-effects-of-dyslexia/

With the aim to assist both parents and educational practitioners to recognise the emotional turmoil that both young and older dyslexics face in life, Neil Alexander-Passe illustrates the lifelong social and emotional effects of dyslexia. The author’s new book Dyslexia and Mental Health: Helping people identify destructive behaviours and find positive ways to cope is out now.

What is dyslexia?

To most, dyslexia is the difficulty with words, but in truth the term is misleading. The true effects of dyslexia go well beyond having a difficulty with words and spelling, as it also affects the ability to remember names and facts, balance and the ability to tie shoe laces and tying ties, misreading and misunderstanding the relevance of numbers, to write neatly, and to recall facts once learnt (even from two minutes ago).

The young dyslexic

The effects of dyslexia are widespread, and in mainstream education everything the dyslexic has difficulty with is valued highly by teachers and their peers. Can they read fast and write neatly? Well, no. Can they remember spellings for a test? Well, no. Can they recall enough facts to write an essay? Well, no. So a young dyslexic will see their friends and peers perform at ‘normal’ rates and progress smoothly through school, and each year the gap widens. Unless teachers have knowledge of special needs and/or dyslexia, it is unlikely that the young dyslexic will be identified as having learning difficulties or differences.

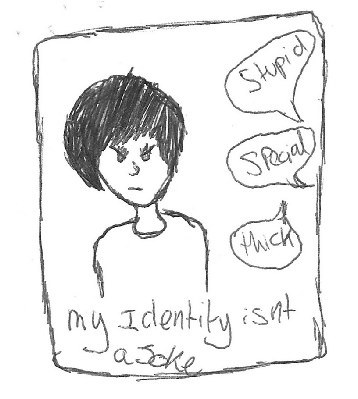

Studies of teacher training courses and the knowledge-bases of teachers support the argument that most teachers are unqualified to recognise a dyslexic child in their midst. So what happens? The dyslexic child begins to see themselves as ‘abnormal’ and ‘stupid’, which is exactly what they are told, either openly by teachers or by their friends, or indirectly by being put on the ‘stupid’ table with the other ‘slow’ kids. Children know who the clever and not-so-clever ones are very fast, and no matter how teachers dress up mixed-ability classrooms, kids know! In the playground the clever kids mix within their own circles, excluding all the others as misfits.

Each year the dyslexic child falls even further behind their peers, and their common reaction is to give up even trying in class, as no matter how hard they try, they always seem to get the lowest marks. No matter how hard they revise spellings or facts, within minutes or hours such facts or spellings are lost like grains of sand.

Emotionally such failure on a daily or hourly basis is harsh. What can the dyslexic child do in such a hostile environment? Well, many withdraw and develop depressive symptoms to cope, as it’s easier that way.

The adult dyslexic

After ‘surviving’ school, maybe without any qualifications to their name, dyslexic young adults are faced with finding a job, or going to college to gain the qualifications they need to start an apprenticeship. They see their peers leave school with 8-10 GCSEs, and all they have is one or two qualifications in unvalued subjects, such as Art or Drama. They see their peers go to university or train up to any career that takes their fancy, but what can the dyslexic do? Do they have a choice? Not with the lack of qualifications they have. Their dreams of being lawyers or doctors are just that, dreams.

Do they either start on a low-level college course to develop their basic skills, take a job in manual labour, or be unemployed – they begin to question their place in society. Can they take their place, or are they excluded from a society that highly values those who can read and write? Once again, they see that withdrawal is a good option to protect their self-esteem, and again depression looms. Many find completing application forms so exhausting that they give up even applying for jobs or benefits, and some even turn to crime to make ends meet.

Dyslexics and their families

Parents of young dyslexics are bemused by their child who can orally seem intelligent but just cannot seem to cope at school. They know they work hard but nothing seems to stick. They know that no matter how long they work at writing an essay, it looks messy and rushed. Compared to their non-dyslexic children, they can see their dyslexic child starting to give up, and beginning to withdraw into a shell-like existence.

The dyslexic child begins to question their place in their family; it is almost like they don’t fit in. They begin to question if they were adopted, and many have been known to write ‘help me’ on signs in their bedroom windows, or even run away from home, as they feel trapped by a family that they don’t feel a part of. What does running away achieve? It manifests their anxiety about fitting in. It says to them that it’s better to leave as they don’t fit in, and that their parents and siblings do not understand them. Many keep a packed bag under their beds, even from an age as young as seven, so when the pressure gets too much, they can flee at a moment’s notice. Where do they go? Anywhere, as it must be better than a home that feels more like a prison.

What can be done?

- Schools need to train teachers to recognise dyslexics in their classes. Research suggests that 20% of all school-aged children will have a learning difficulty at some point in their education, and dyslexia is the single most common difficulty. Seen severely in 5% of schoolchildren and another 5-10% more mildly, that’s at least one to two dyslexic children in each classroom.

- Teacher training needs to teach recognition of learning difficulties.

- All teachers are required by the UK government to be qualified to teach all children with special educational needs in their classrooms, but most lack this ability, so additional training is urgently required for them to ‘differentiate’ their lessons effectively.

- Schools need to identify early and provide specialist teaching to children with special educational needs.

- Schools need to provide counsellors for children who experience difficulty learning at school, as the emotional effects of failure can lead to social exclusion, depression and self-harm.

- Teachers need to recognise the avoidance by children, ask themselves why, and act to question if there is a learning difficulty or another barrier to their learning e.g. avoiding reading and writing.

- Parents need to praise the effort not the end result, and support their children to focus on strengths not weaknesses.

But don’t some dyslexics survive school and succeed in life?

Whilst it is true that some dyslexics do well in life (e.g. Richard Branson, Keira Knightley, Mollie King, Jamie Oliver, Tom Cruise), researching them you hear the same thing. School was hell and they left as soon as possible. They also highlight that they found something they were good at early on, maybe not school subjects such as English, Maths or Science, but vocational skills such as selling, persuading, acting, cooking, art and design, etc. This allowed them to balance the negativity at school with their ability to out shine their peers outside school. Ongoing research in dyslexia and success has found that each successful dyslexic has a ‘chip on their shoulder’ to prove everyone who ever doubted their ability wrong, to prove that they are not ‘stupid and thick’. They are driven by their school failure and humiliation to do well in life. Even returning to school for their own children is hard for them, they can have symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder when seeing small chairs, smelling sickly floor cleaner, or seeing drawings pinned up on walls, as theirs were not deemed good enough for presentation.

Dyslexics, unless diagnosed and helped early on in their school career, will suffer from varying levels of emotional pain. Be it low self-esteem, self-doubt; withdrawal or running away from home. It is important to recognise that secondary bad behaviour is commonly covering up for primary difficulties, but most teachers are just satisfied by mislabelling pupils as troublemakers and try to move such needy pupils to a different teacher.

Neil Alexander-Passe is the Head of Learning Support (SENCO) at Mill Hill School in London, UK, as well as being a special needs teacher and researcher. He has taught in mainstream state, independent and special education sector schools, and also several pupil referral units. He specialises in students with dyslexia, emotional and behavioural difficulties, ADHD and autism. Neil has written extensively on the subject of dyslexia and emotional coping and, being dyslexic himself, brings empathy and an alternative perspective to the field.

| About the Author |

| Academic CV |

| Teaching CV |

| Research for the book |

| Reviews for the book |

| The Successful Dyslexic Book |

| How can parents support their child with dyslexia? |

| Dyslexia, self-harm and attempted suicide |

| The Lifelong social and emotional effects of Dyslexia |

| Dyslexia and Depression |

| Dyslexia: Dating, Marriage & Parenthood |

| Dyslexia and Creativity |

| Dyslexia and Mental Health-differing perspectives |

| Dyslexia & Mental Health |

| Surving School as a Teenage Dyslexic |